Oregon’s Shakedown versus Maine’s Focus on Compassionate Care

When the Going gets Tough, the Tough Tax the Poor, the Sick, and the Elderly

By Mary Lou Smart

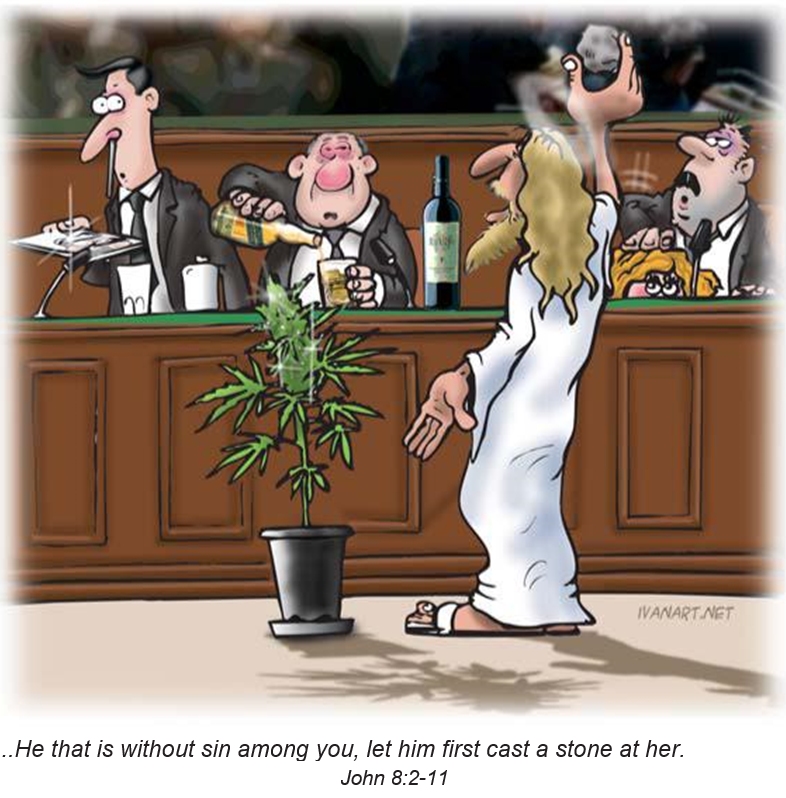

Those who push taxation of cannabis as a means of easing America’s most popular cash crop into the mainstream might be selling out society’s neediest.

Oregon’s medical marijuana program is an example of how short-sighted strategies derail long-term potential.

The Oregon Medical Marijuana

Program (OMMP) man- dates that an advisory committee monitor, and have input in shaping,

any legislative changes affecting the

program. This past June, by working through a

ways and means committee, the legislature circumvented the law when

they deliberately kept information about a fee hike away from the Advisory

Committee on Medical Marijuana (ACMM).

With state revenues falling, the legislature did not want the state’s strong cannabis advocacy movement gumming up the works of a blatant money grab. By keeping those about to be gouged out of the discussion, the sick would be easy prey.

Sandee Burbank is executive director and co-founder of Mothers Against Misuse and Abuse (MAMA), an organi- zation in existence since 1982 that is focused on responsi- ble drug decisions. MAMA operates three clinics, and has been involved with Oregon’s medical marijuana program since its beginning in 1998. Burbank is in her second four- year term with the ACMM.

ACMM is an 11-member,

volunteer committee on the ground floor of the Oregon Department of

Human Resources, which oversees the Oregon

Public Health Division, which oversees the

Oregon Health Authority (OHA), which

oversees the OMMP, which

is mandated by law to have

and work with an advisory committee. At

the time

of the increase, an administrator with the OHA doing a three-month stint as interim director, Barry

Kast, decided to keep the committee in the dark when attending its June 6 meeting, two days before legislature voted.

“It was just a shock,” said Burbank. “Barry Kast admit- ted in the taped meeting that we had afterwards, and it’s in the minutes of our meeting, that he is the one that made the call to keep the information from the ACMM, because he was afraid that we were going to hurt the Oregon Health Authority’s relationship with the legislature. He said that he didn’t think that the legislature knew much about the program. They don’t know about the program, because we were not even allowed to come in to testify about the program. How this could even have happened without public hearings is amazing.”

So the annual fee for a medical marijuana card in Oregon just went from $100 to $200. There are other add-ons, and eliminations of discounts for the disadvantaged, that will make many think twice before paying this regressive tax.

“This is a straight-out tax, and

the way it went down is terrible,” said Burbank.

OREGON’S SHAKEDOWN VERSUS MAINE’S FOCUS ON COMPASSIONATE CARE

For patients,

there is considerable frustration in knowing that the only funding for Oregon’s

medical marijuana program, the registry, is being siphoned out. Greig, a board

member of Voter Power Foundation, an advo- cacy group that operates three

patient clinics, has watched the parasitic behavior of the legislature since

the program started.

Oregon’s medical marijuana program recognizes four cat- egories of cannabis entities; patients, caregivers, growers and grow sites. A patient needing someone else to grow product now has to pay the $200 card fee plus an extra

$50 grow fee, meaning that the neediest patients, those who for one reason or another cannot grow their own medicine, will now pay $250. A sliding scale for low- income patients was also ratcheted up.

Increased fees add to the burden being dumped on patients. Growers are only allowed to grow for four patients. If the grower moves, causing these four patients have to find a new grower, each patient must submit a notification-of-new-grower change to the OMMP and pay a fresh $100 change fee. If the grow site moves and the patient has to find a new grower, the patient pays the

$100 change fee. Every time a patient loses a card in raids taking place around the state, the patients must pay $100 to have a new card issued. The $100 change fee applies to lost and stolen cards. These are all new fees for reissuing cards.

For being on Oregon’s registry, a patient receives zip; the registry provides no services. To avoid the inconvenience of having to continually authorize the raiding of funds originally designated for the operation of the OMMP, the legislature is now just taking funds outright.

According to Christine Stone, communications officer, Oregon Public Health Division, the latest fee hike for being on a medical marijuana registry will go directly from the OMMP into the coffers of the OHA to fund Public Health Division programs such as clean water, sen- ior food services, emergency medical services, and school- based health centers.

Funding from the original portion of the fee, prior to this sin tax on the sick, is used to pay for 36 permanent and temporary employees who maintain the registry and col- lect the fee. Program enhancements focus on data collec- tion, not anything even vaguely resembling patient servic- es. Most patients are learning of the fee hike as they receive their renewal notices in the mail, as the bare-bones department is apparently unable to keep anyone up to date on current events.

Stone readily admitted that the

OMMP had no say in the increase.

“This came to us directly from the legislators,” said Stone. “These are tough budget times. People are not working, and they’re not getting the tax dollars. They saw this pro- gram as a way to fund about six of our programs that oth- erwise would have lost significant amounts of funding.”

Jim Greig, 51, is a patient with rheumatoid arthritis so advanced that most of his joints are swollen to the point of being dislocated. He’s been wheelchair bound for 20 years, and is confined to a hospital bed 80 percent of the time. With cannabis, he is not reliant on heavy narcotics for pain relief. Due to inactivity, he suffers from muscle spasms in addition to pain. Tincture of cannabis stops muscle spasms in their tracks. He has another condition similar to glaucoma that results in painful inner ocular pressure, which, until he realized that cannabis would work, could only be relieved with a shot of cortisone directly into his eyeball. A pleasant side effect of his ongo- ing cannabis therapy, he reports that his eyes have not been swollen in 10 years.

Like most patients who have a vested interest in seeing the program succeed, he viewed the fee hike as underhanded.

“We were watching for bills that might be restrictive of the OMMP,” he said. “This was a budget bill, and so it scoot- ed along through the process without any of our normal activists or legislative watchdogs spotting it. We were there for the final hearings, but by that point the mind set was already made up.”

For patients, there is considerable frustration in knowing that the only funding for Oregon’s medical marijuana pro- gram, the registry, is being siphoned out. Greig, a board member of Voter Power Foundation, an advocacy group that operates three patient clinics, has watched the para- sitic behavior of the legislature since the program started.

“They’re not putting a nickel into research, or into any of the other suggestions that our mandated advisory commit- tee gave them,” he said. “We have an advisory committee made up primarily of patients, and they really ignore all of their suggestions. This is not just a temporary budget fix, either. It’s in for good.”

One of the suggestions ignored, according to Greig, was the idea of boosting fee income with additional health issues, such as post traumatic stress syndrome, added to the list of conditions approved for a physician recommendation.

“We’re not used to getting much love from our state leg- islators,” he said. “The irony is that they are charging poor people to fund government programs for poor peo- ple. They didn’t raise the fee for the fishing license, driver’s license or hunting permit.”

The registry that gives zero to patients is targeted as a rev- enue source by a cash-strapped government, a strategy that patients see as failing over time.

Oregon’s medical marijuana program was designed to pay for itself, and that is why the registry fees were initially imposed. The annual fee was first set at $100, with a slid- ing scale for the neediest. At first those receiving Social Security Income (SSI) paid only $20. Eventually, thanks to the efforts of the ACMM, recipients of Oregon Health Plan or food stamp aid also received the low-income, $20 rate. While the state boasts of the reduced rates for the needy, only about 700 of Oregon’s registered patients — 53,685 in August — receive the lower rate, according to Burbank. Low income patients in the Oregon Health Plan and those receiving food stamps are learning that they will now pay $100 for their annual fee, and if they need a grower, thanks to the $50-a-year grower fee, their annual fee has been jacked up to $150 from $20. SSI patients remain at the $20 level, with an additional $20 for a grower other than themselves.

In its capacity as an advisory committee, the ACMM meets four times a year to review the OMMP’s budget and receipts. Several years back, when the fledgling program was running a surplus, the committee recommended low- ering the fee to $55, which did occur. But then the legisla- ture came in and authorized transferring a few hundred thousand of the surplus to the Department of Human Resources, and the fee had to be moved back up to $100 to make up the difference. Following that, the legislature came in and took almost $1 million of the surplus, this time transferring it directly to its general fund.

“The whole program has been overpriced from the begin- ning,” Greig said. “When we first sat down to discuss it, when the program first started, our goal was to keep the fee as low as possible, $100, and the low-income fee as low as possible, $20. At the end of those initial meetings, we were assured that if there were surplus funds, we could always meet and adjust them accordingly. Instead, the funds were appropriated by our legislature. They’ve already taken nearly $2 million out of the program, and now the goal is $7 million over the next two years.”

So you have a patient-funded

registry providing no servic- es, and an advisory committee mandated by law

that is kept in the

dark and ignored.

According to Cheryl Smith, executive director of the Compassion Center in Eugene, many in the legislature who understood that the increased fee would be a hard- ship on patients, pushed it anyway to discourage patients from supporting the program.

“To me it seems like such bad faith that they have done this,” she said

The Compassion Center helps patients meet with physi- cians willing to consider cannabis as a medical treatment option. Seeing approximately 1,300 patients a year, the clinic has its own set of fees, including $60 for the exam of a new patient, $45 for a renewal, and a doctor visit with a physical for $160.

“So right there, a patient is paying more than $200, and the state’s charging another $200, and now they’ve added on the grower fee,” she said. “This is an underhanded way to stop the program, in my opinion.”

Burbank, who has nothing but praise for those working at the OMMP, is jaded by the Oregon legislature’s tactics.

“In all of my years of dealing with the legislature, I’ve never seen them be able to make these types of changes without public hearings,” she said. “After 30 years, I almost said the hell with it. I can see little, itty bitty things going in the right direction, but then things like this occur that are so sneaky and underhanded. It’s horrible.”

Cannabis is decriminalized in Oregon to the point where fines are minimal. In addition, the state is one of the few that have moved its classification of cannabis from Schedule I to Schedule II in recognition of its medical benefit.

Oregon’s legislature, which has a deeply-entrenched med- ical marijuana movement that is not going away anytime soon, appears to be recklessly destroying an opportunity for revenue growth by bleeding a program dry. When a medical program designed to care for the sick demands more and more without providing anything in return, who wins?

In a state that does not even have dispensaries offering product, there’s not a whole lot of incentive to keep buy- ing a card to be listed on a registry unless you are too sick to grow your own or unable to get out of bed to buy it on the black market. The Oregon medical marijuana registry fee is an incredibly regressive tax falling on the backs of society’s neediest.

“There are an awful lot of card holders that do not renew,” said Greig. “The reasoning is, “Why should I? The cops never hassle me, and the card got me nothing.”

Maine’s Proactive Strategy

At the other side of the country, legislators in the state of Maine have chosen to support a medical marijuana pro- gram that protects patients. In June, while Oregon’s legis- lature was hiking fees without input from the patient com- munity, Maine’s Governor Paul LePage signed into law a bill aimed at protecting the privacy of medical marijuana patients. In approving Republican representative Deb Sanderson’s bill to eliminate the state registry, the legisla- ture also ensured access and clarified and enhanced law enforcement protections for patients, caregivers, doctors and dispensary employees. The Maine law eliminates mandatory state registration and mandatory disclosure of a patient’s specific medical condition to the state Department of Health and Human Services, and creates a more workable means for adding approved conditions. It also prohibits arrest for qualifying patients, caregivers and dispensary employees acting under the law.

Maine’s registry is voluntary for patients. Also self-suffi- cient, the state’s medical marijuana program is able to fund itself by collecting fees from dispensaries and some care- givers. Caregivers growing or buying cannabis for family members or household members do not have to pay a fee.

Patients pay no fees when voluntarily registering with the state, something that many choose to do when they are not worried about being stigmatized or harassed, an example given is the case of an older glaucoma patient who might like to carry more credible identification than a doctor recommendation to show if he or she is pulled over.

In eliminating mandatory registration, Maine’s leg- islators were looking out for patients.

“Our biggest concern was patients being forced to reg- ister in a state-wide database,” said Alysia Melnick, an attorney with the ACLU of Maine who helped to draft the bill. “They were being required to submit personal and confidential medical information to the state. Databases can always be breached, and that is highly concerning.”

Maine’s program is fairly fluid, allowing patients to shift easily between growing for themselves or accessing medi- cine through a caregiver or dispensary. Another goal in building Maine’s program was looking out for its success, according to Melnick.

“If you make the laws so costly or cumbersome that patients cannot afford, or are too fearful, to partici- pate, then they are just going to continue to use the black market,” she said. “What we don’t want is seriously ill patients being arrested and prose-

cuted for trying to treat their pain and suffer- ing. That is why states pass these compassion- ate medical marijuana laws in the first place.”

Fewer Renewing in Oregon

Back in Oregon, fewer are renewing according to Burbank who said that poorer patients simply cannot afford the increased fees. An optimist by nature, she dug deep to find a sliver of a silver lining in the constant siphoning of cash from the state’s medical marijuana registry.

“The only good thing that I can see coming out of this is a growing aware- ness of how much money can be raised, and saved, if we were to legal- ize cannabis for adults,” she said. “They are going to be dependent on us now, for raising all of this money year after year, and they are going to want more.”