Post-Traumatic Syndrome A Natural Response to Trauma

Mary Lou Smart www.medicalcannabisart.com

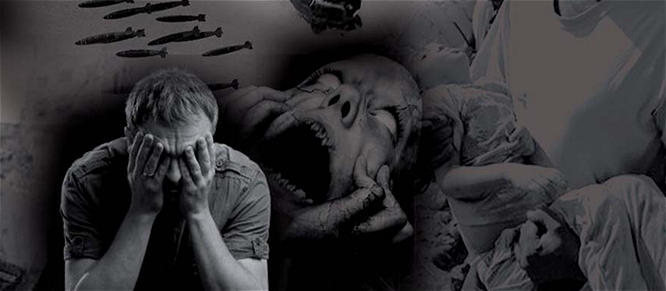

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Association, defines post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to an extreme traumatic stressor.

Reactions include helplessness, fear and horror.

Persistent memories of the event, or events, lead to dreams, nightmares, obsessive thoughts and flashbacks (actual recreations of an event).

While the walking wounded suffering from life’s traumatic episodes are every-where, military veterans experience post-traumatic stress in higher numbers and therefore receive more press.

Viewing it as a natural response to unnatural events, Mary Lynn Mathre, RN, CSN and CARN, a Vietnam-era Navy nurse and president and co-founder of Patients Out of Time, says that she’d be more curious about combat veterans who return from war without post-traumatic stress syndrome. Patients Out of Time is the leading educator for health care professionals and the public on the therapeutic use of cannabis.

“Frankly, if you talk to a lot of the vets, if they go to cannabis, they do so much better,” she said. “A lot of the vets coming back are committing suicide. This is a huge story that needs to be told.”

Drugs Aplenty for the Traumatized

In February, The New York Times published a story written by James Dao about the United States Veterans Administration (VA) dispensing a cornucopia of prescription drugs to soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan with PTSD diagnoses.

Many are also on pain medications, and many are mixing, matching and self-medicating. With easy access to the likes of Ativan, Adderall Ambien, Celexa, Effexor, Elavil, Haldol, Klonopin, Lunesta, Prozac, Paxil, Restoril, Risperdal, Ritalin, Seroquel, Trazodone, Valium, Wellbutrin, Xanax and Zoloft, many who are trying so hard to cope end up dying. These deaths are often labeled as accidental. None are being treated by the VA with cannabis, the only medication that’s never killed anyone and has long been associated with weaning patients off of strong nar-cotics.

The VA’s been sending returning vets out on the streets with loads of prescription medications for decades. Its own personnel report a shortage of counselors to treat veterans and a lack of resources to track the multiple medications. Although in recent directives it acknowl-edges that veterans in states with medical marijuana programs will be permitted to use cannabis in tandem with medical treatment offered through the VA, for the most part this federal entity refuses to acknowledge the medicinal benefit of cannabis.

Despite decades of clinical studies overseas that have convinced authorities in other countries to treat wound-ed soldiers with cannabis, the federal government con-tinues to classify marijuana as a Schedule I drug with no medical benefit under the Controlled Substances Act.

“Israel and Czechoslovakia are using it for their soldiers right now,” said Al Byrne, co-founder of Patient’s Out of Time, past executive director of NORML, Vietnam vet-eran and retired Navy officer. “They’ve decided that the therapeutic value is so great that their soldiers can have it. These are the same guys that our guys are fighting next to in Afghanistan. They get hurt; they get cannabis. Our guys get hurt; they don’t get cannabis.”

Michael Krawitz, founding director of Veterans for Medical Cannabis Access, is a 100-percent disabled Air Force vet injured in the1980s who experiences consider-able pain. Over the years, his knowledge of standard pain treatment has grown along with the pain medica-tions he has been prescribed. He hated Ultram, a syn-thetic, narcotic pain killer whose negative side effects were “so horrible that they made taking the medication unbearable.”

“With easy access to the likes of Ativan, Adderall Ambien, Celexa, Effexor, Elavil, Haldol, Klonopin, Lunesta, Prozac, Paxil, Restoril, Risperdal, Ritalin, Seroquel, Trazodone, Valium, Wellbutrin, Xanax and Zoloft, many who are trying so hard to cope end up dying.”

After his Ultram experience, he insisted on researching each new drug before agreeing to take it, which he did when Amitriptyline was offered. He told his doctor that the negative side effects that he’d read about – seizures, dizziness, drowsiness, impaired think-ing, sexual complications, suicidal thoughts and fatal reactions when combined with other drugs – made him reluctant to use it. With Ultram, the warnings he’d read stated that up to 40 percent of the patients taking it experience the same side effects. A series of other med-ications came with similar warnings. He also refused to take Vioxx, Celebrex and Lyrica.

To counter the depressing aspects of pain medications, he was given antidepressants. “When I first started being treated as a disabled vet at the VA in Omaha, they rou-tinely gave me huge jars of Zoloft, antidepressants, with my pain killers,” he said. “They just automatically give you Zoloft; they just automatically do, probably a lot of hospitals do, to counter the depressive effects of the nar-cotics.”

Krawitz read about Zoloft and decided not to use it. “I looked them up in the book and the effects seemed to be less than the cannabis could provide, so I never took them up. I just used cannabis.”

The Land of Enchantment

Numerous studies point to the endocannabinoid system’s strong role in regulating emotions. Such studies, along with considerable patient testimony, convinced lawmakers to include PTSD as the only psychiatric indication qualifying for a recommendation in New Mexico’s medical cannabis pro-gram.

Bryan Krumm, psychiatric nurse practitioner, is on Patient Out of Time’s advisory board and has spoken at its biennial conferences. He has petitioned the federal government in an effort to have cannabis moved from Schedule I to protect patients as well as medical professionals. Krumm helped draft New Mexico’s medical cannabis legislation, pushing for the addition of PTSD as an approved condition. New Mexico’s is the only medical cannabis program in the United States recog-nizing PTSD as a qualifying condition.

“In terms of safety, there is nothing that we have to offer phar-maceutically that can match the safety of cannabis,” he said. “In my own practice as a clinician, I have never come across a single pharmaceutical agent that is as well tolerated, and lacking in significant side effects, as cannabis.”

Many of Krumm’s patients suffer from post-traumatic stress. The greatest number of people applying for a recommenda-tion in New Mexico receive it for post-traumatic stress. As of February 16, PTSD was the qualifying condition for 1,105 of New Mexico’s 3,218 medical cannabis patients.

“I’ve seen some very significant benefits in helping with that, which go above and beyond what I’ve been able to do with just traditional pharmaceuticals,” he said. “Probably the vast majority of patients that I have in the program still require pharmaceutical treatment. But quite often the traditional pharmaceuticals are not able to manage the anxiety, not able to stop the nightmares, the flashbacks, the constant, recurring thoughts that people get, and that’s where cannabis is very helpful.”

Animal studies point to hyperactivation of the amygdala, the part of the brain involved in emotional regulation. Shown in research to perform a primary role in the processing and memory of emotional reactions, the amygdalae have a large number of cannabinoid receptors, as do other areas of the brain feeding into them.

“Activating those receptors helps turn off or slow down the hyperactivity,” Krumm said. “So we see things like a decrease in anxiety, a lessening of depression. With patients with chronic suicidal behavior, we’ve seen it take away suicidality when they would not remit with traditional pharmaceuticals. Another big thing, with PTSD we see mood swings with irri-tability and anger. Cannabis really helps to control that. It has the advantage of working very quickly when working with the inhaled route in being able to suppress those types of emotions and allow people to function better.”

Therapeutic Benefit

Pushing to have the D taken out of PTSD, Patients Out of Time would rather see it called post-traumatic stress syn-drome.

“This is a natural response to an abnormal stress, so why do you call it a disorder?,” Mary Lynn Mathre asks. “It’s post-traumatic stress. It’s a syndrome. To call it a disorder adds insult to injury. This is what happens when you real-ly are stressed with something above and beyond normal day-to-day stressors.”

For extreme emotional trauma, Mathre says that cannabis therapy is a safe solution.

“The basic science is showing that cannabis helps with the forgetting,” she said. “It helps patients to calm down.”

Ervin Dargan’s seen the connection between his stuttering and post-traumatic stress syndrome.

Less than one percent of stutterers carry the condition into adulthood. Dargan’s anxiety over past and future speech was great, which only exacerbated his torment.

“If you’re traumatized by an embarrassing episode of stuttering, you tend to dread it,” he said. “It becomes a cumulative stress that stays. I was one of the ones that didn’t grow out of it.”

There is no known cure for stuttering. Its impact can be severe, causing ongoing feelings of shame, embarrassment and frustration.

“Stuttering is a tough nut to crack,” he said. “I went to speech therapy when I was a teenager, and that didn’t seem to work. You can wear headphones, and that seems to work, but it also seems that most things for stuttering work for a little while and then they don’t.”

While Dargan is quick to distinguish between the severity of war and his experiences, he feels that the end result of trauma can be similar.

“The vets definitely deserve to have their post-traumatic stress up there, up front, but there definitely are others that deal with the effects of built-up stress,” he said.

For Dargan, 54, cannabis is the only treatment he’s tried that has provided lasting benefit. While occasionally smoking heavily-seeded, low-grade marijuana in the 70s and 80s, he noticed that it seemed to help his speech. In the late 1990s, visiting friends who consistently smoked strong weed, he realized the full benefit of high-quality, seedless, sinsimellia product, which did the trick. He’s stuck with it ever since.

“If I give it up for awhile, I notice after about a week that my tension starts to rise again and I start to stutter more,” he said.

Dargan’s experience instilled a desire to advocate for patients and medical cannabis. A videographer by trade, he combines his skill with patient / writer, Mark Pedersen, in documenting personal profiles on www.cannabispa-tientnetwork.com. He also films and provides website support for Patients Out of Time, www.medical-cannabis.com.

“I tell people that I’m thankful that I was a stutterer because it helped me to communicate,” he said. “I look ahead in a conversation to think of words. When you stutter, the desire to communicate is overwhelming because that’s the one thing that you can’t do. It can be extremely frustrating, but I think the overall experience helped me to communicate better.”