Watching the Grass Grow in Rhode Island

Mary Lou Smart – www.medicalcannabisart.com

Ellen Lenox Smith finds growing cannabis to be therapeutic. That’s a good thing, as Smith is in constant pain, and access to medicine is limited in Rhode Island.

“Once you find someone who knows how to grow mar-ijuana and who will teach you to grow, it becomes a very pleasant part of life,” she said. “I have to ride a stair lift down to get to the cellar, and then I’m able to take care of these plants. It gives me something to do when I’m not feeling well. I’m enjoying it now, but this is a big part of my life, and it has to be done. This is my medicine.”

Smith, a mother of four sons and former middle school teacher and swim coach, wants to share her story.

“Medical marijuana needs a face,” she said. “Everyone should see that we are real people who had bum luck with health. We’re fighting a society that is seeing this as a recreational drug. I’m just an everyday person. I’m 5’2”, 96 pounds, and I’m struggling. I’ve tried to live a good life. People who know me and see me suffering and going through this stuff, well, it just helps them to change their attitude. People that know me do not want to see me in pain. And when they hear that this is what I’m on (cannabis), it helps them to not get scared.”

“Without dispensaries, the key is to become self-sufficient and to develop a reliable network of advocates, patients, and medical professionals.” according Smith. She has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) and sarcoidosis.

EDS is a connective tissue disorder caused by a defect in the development of collagen that shows itself in orthopedic issues and basically causes bones throughout the body to become unglued. She likens her body to a rubber band becoming overstretched. If someone accidentally knocks into her in passing, ribs can and do pop out. If someone hugs her, the vertebrae supporting her neck occasionally slip out of place. The inherited disorder is difficult to diagnose because those afflicted with fragile ligaments and tendons often look normal. Finally pin-pointed in 2004, her progressive condition has resulted in 19 surgeries throughout her life.

Finding marijuana has been part of her medical journey. She never considered the plant; her pain physician did. One of the many challenges for Smith is that she’s aller-gic to prescription painkillers.

“I’ve been given a body that will experience increased pain for the rest of my life and I cannot tolerate most pain medications,” she said. “I can’t even take aspirin or a Tylenol.”

In constant pain, a tremendous and growing problem for Smith was a lack of sleep. One rare result of Smith’s EDS is a floppy trachea, which means that her trachea might bend and her sternum might slip, and she can stop breathing while sleeping. A home respirator and a very attentive rescue dog were helping, but her two chronic conditions and intolerance of prescription medications were preventing anything close to a good night’s sleep.

After having a bad experience with marijuana in college that created anxiety instead of euphoria, she had never given it another thought. When her doctor mentioned that it might help her pain so that she could nod off to sleep, she almost fell off her chair. He suggested that since no legal means to acquire a test sample were in place, maybe one of her sons might be able to find some so that they could establish whether or not it would provide relief.

“It was scary for me because I’d had a bad reaction, but I had to turn to something for help,” she said. “I had nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

With her black-market marijuana, Smith was ready to roll, although with sarcoidosis manifesting itself in her body as a chronic lung disorder, she was unable to smoke. Instead, she quickly learned how to heat the ground-up leaves with extra-virgin olive oil, 10 table-spoons’ product to one cup of oil.

“I tried a half-teaspoon full the first night, and couldn’t believe it,” she said. “I actually slept the entire night. I had not had that luxury in ages.”

Although her doctor, Pradeep Chopra, MD, had not planned on giving any patients a cannabis recommendation, when she told him that it had helped her to sleep, Smith became his first recommendation to the state pro-gram. Three years ago, she was approved. Her first challenge was in finding a legal supply. These days, she grows her own. Despite constant pain, the 60-year-old is upbeat and ener-getic.

Chopra recommends cannabis when other medications are not working.

“Marijuana does not work in the same way that opiates work,” he explained. “Cannabis has a whole different mechanism of action compared to opiates, and so you are using two different techniques to control the same pain. All of my patients have told me that it helps to tolerate their pain much better. Not too many of them tell me that it takes care of their pain. It’s just that they tolerate their pain much – ter and they get to be more functional.”

Without dispensaries, Rhode Island network to provide each other advice. Bobbie Clark (not his real name) told Smith that she’d benefit from a vaporizer, which would provide faster relief during the day than the long-acting tinctures she uses to sleep. She occasionally grows cannabis for him.

Clark, 58, also tried cannabis as a last resort. Nine years ago, he’d fallen from a roof, been impaled on a tree stump, and was paralyzed.

“This has all been very hard on my wife and my children and myself,” he said. “My wife doesn’t want my family to know or to think I’m a pothead, but if more people would come forward and admit that they do this, espe-cially well-known people, things would change.”

Clark was at the end of his rope when Chopra suggested that he speak with Smith. Chopra has grown accustomed to mixed reactions following his suggestion that cannabis might provide relief. He’s come to rely on Smith with patients that he feels might benefit from cannabis thera-py. “Ninety percent of the people worry about what their families will think,” he said. “If I bring up the subject of medical marijuana with a patient, obviously there is some hesitation, and so what happens is that I tell them to talk to Ellen. When information is coming from me, it is coming from a physician. My advice is clinical, unemo-tional. Ellen is a patient that they can relate to; a woman who has the same types of pains and who is active and functional.”

was in constant, excruciating pain. Conventional pain therapy was not working. Because of his injury, his pain medication was not being properly absorbed into his body; much of it was passing directly into a colostomy bag.

“His was getting out of control and it was getting the better of him,” said Chopra. “We’d tried many things, and nothing was working. He became more and more depressed, and his health condition started to deteriorate con-siderably. For a paraplegic to exercise, it requires not only superhuman strength; it superhuman mental effort. At times, I would give him a hug in the office in the sense that he and I knew that we might not see each other again. That’s how bad it was.”

worries about the social stigma of marijuana, Clark and his wife went to see Smith. Shortly thereafter, he started using His spirits improved and he became functional again.

“If you could see how many pills I’ve stopped taking because I’m taking mar-ijuana,” he said. “Through the grapevine, trying to put my life together, I found a guy with a vaporizer. I had a chance to smoke marijuana so many years ago and I said, ‘No way. No way. No way.’ Now, come to find out, I don’t even need to smoke it. With the vaporizer, the flame never touches the leaf. It’s very soothing, so it’s good for your lungs.”

After Smith’s pain was under control, she wanted to do as much as possible to get the word out.

“She came to me and said that she’d like to be a produc-tive member of society and asked what she could do,” Chopra said. “I said, ‘Well, you can be an advocate for pain patients.’ I think that those are the best spoken words that I’ve ever spoken in my life.”

“The problem,” he continued, “is that right now, we have a generation that grew up being told that this is a bad drug, and we have a generation growing up saying that this is acceptable. So we are at a crossroads with the generation that grew up learning that this is a bad drug needing it the most.”

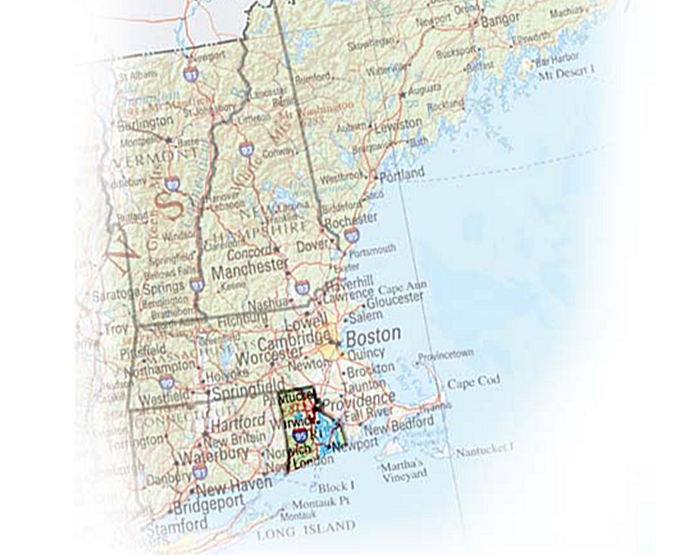

Rhode Island Gov. Donald L. Carcieri did not want a medical marijuana program. That’s one theory behind why after four years, the state still has no means in place to supply a growing number of patients with even one compassionate use center to buy medicine. His veto of the program was overruled. The rumor goes that muscle from this former top dog explains why the Rhode Island Department of Health has rejected all applications to date, including 15 in early 2010. Another 21 applications were submitted at the end of 2010. Many are hopeful that with a new governor in office, Lincoln Chafee, the administration’s focus will be on patient well-being once again.

Despite the politics, Rhode Island supports medical cannabis. It was approved in January 2006, not by voter referendum, but by the state legislature following the endorsement of the medical community and testimony by patients. After the vote to create a program, subse-quent compassionate use center legislation, which gave the go-ahead for up to three dispensaries, was approved by 96 percent of the legislature. Momentum grew quick-ly; the state has 3,040 registered patients and 1,942 reg-istered caregivers.

The Rhode Island State Nurses Association (RISNA) supports the Safe Access to Therapeutic Marijuana poli-cy of the American Nurses Association (ANA). The pol-icy is embedded in the organization’s ethics and human rights statement. RISNA cosponsored “Cannabis: The Medicine Plant,” Patients Out of Time’s 2010 conference, held in Warwick, Rhode Island, in April. In atten-dance were 320 MDs, RNs, dozens of PhDs, and patients. The conference was approved by the American Medical Association (AMA) and the ANA for continuing education credits.

Executive Director Donna Policastro, RISNA, presented the opening statement and welcomed attendees and speakers, some of whom came from as far as Canada, Brazil, and Israel. She said that RISNA helped lobby and testify for Rhode Island’s legislation and that the support of the Rhode Island Medical Society (RIMS) also helped to move the legislation forward. RIMS is a voluntary association of physicians, physician assistants, and med-ical students deeply rooted in the community, with a his-tory dating to 1812. She concluded by stating that RISNA was looking forward to the compassionate use centers, and hoped that it could include them in a pri-mary care services guide in 2011.

“It’s an access issue, it’s a safety issue, we believe very strongly in it, and we want to move forward and contin-ue to be proponents of this issue,” she said.

Throughout the state, from patients to medical profes-sionals and advocates, stories of benefit and support abound.

“From the get-go, acceptance of the medical marijuana program has never been restricted to a fringe element,” said JoAnne Leppanen, director, Rhode Island Patient Advocacy Coalition (RIPAC). “We have everybody. In Rhode Island, things are very personal. Everybody knows somebody who is in the program or should be in the program. It’s been seen as something that everybody might need. If you don’t need it now, how many of us are going to get on in life with a debilitating medical condition that might benefit from medical marijuana?”

The greatest challenge in the emerging program is access, according to Leppanen. Patients approved into the pro-gram are permitted to grow cannabis or to appoint up to two caregivers to grow plants. Getting set up, however, takes awhile.

“Patients get into the program and ask, ‘Where’s my medicine?’” she said. “If you’re going to grow it on your own, that can be fine, but some people are too sick. Some people have no housing. Even if they have the means to grow plants, growing cannabis takes time.”

She’s praying that the current go-round of applications is viewed in a more positive light.

“My fingers are blue, they’re so crossed,” she said. “This is a huge challenge for some people. They tread water until they can get a consistent supply.”