Top-Down Tactics Stall Legal Access to a Natural Remedy in the Garden State.

In New Jersey, conditions approved for a cannabis recommendation are: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; multiple sclerosis; terminal cancer; muscular dys- trophy; inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease; and terminal ill- ness, if a physician determines a progno- sis of less than 12 months of life. If resist- ant to, or if the patient is intolerant to, conventional therapy, seizure disorder, including epilepsy; intractable skeletal muscular spasticity; and glaucoma are also approved. In addition, HIV, AIDS and cancer apply if accompanied by severe or chronic pain, severe nausea or vomiting.

For many with neuropathic pain, conventional treatment consists of heavy doses of narcotics, which make it tough to get through the day, let alone to work.

“This is a shame because I can go out and get any power- ful and potent pill there is whenever I get my prescriptions refilled, but I chose not to do that because of the effects and damage of those pills,” O’Brien said. “I prefer the safe and natural way. Everything else just clouds my mind and the pain is still there. Cannabis takes the pain away, and allows me to function in a normal and productive way.”

Because the science supporting

cannabis as an analgesic for

neuropathic pain is considerable,

many state medical cannabis programs include it as a condition qualifying for

New Jersey’s medical marijuana program, known as the most restrictive in the U.S., was signed into law in January 2010, and has stumbled along ever since. Patient registra- tion opened recently, and 329 had begun enrolling by October 2012. Many will not enjoy the protection of legal access, however, as the state’s “compassionate care” pro- gram is not focused on the sick and suffering.

Jack O’Brien was born without fingers and toes. Nerve issues stemming from the missing fingers and toes leave him in pain all of the time, especially when he’s trying to sleep. His deformed feet are good for short walks, but the pain is getting worse as he ages. At 58, the former boat captain is completely disabled.

“My electrical system is messed up,” he explained. “The nerve endings in my fingers and toes affect my entire body, and the electrical system in my body is messed up because of it. When my neuropathic pain starts hitting in little beep increments, my muscles spasm and tighten up.”

Because O’Brien’s primary problem is constant pain, his medical records reflect pain. His primary care physician never documented the muscle spasms. “Whenever I have gone in to see her, I complain about the pain in the back of my legs and the back of my arms and up my back,” he said. “Her records reflect the pain.”

In New Jersey’s fledgling medical marijuana program, severe or chronic pain was removed as an approved con- dition just before the law was passed. At the time, the rea- son given was that pain is too broad a condition and too difficult to verify. A few months ago, O’Brien visited one of the few doctors listed on the state’s program registry. The doctor collected $400 for the visit, but told him that since he has no documented spasms he is ineligible for a cannabis card.

That doctor told O’Brien that his $400 fee was necessary to cover the exorbitant cost of all of the equipment required by New Jersey’s Department of Health and Senior Services (DHSS) to transfer and track patient infor- mation. “That just sounds bogus to me,” he said.

Advocates are pushing to have neuropathic pain admitted as a qualified condition. The law states that new condi- tions can be added, but Gov. Chris Christie, who replaced the governor that actually signed the legislation into law, oversaw the adoption of rules and regulations that stalled the program’s launch by almost two years. The new rules complicate the procedure for adding new conditions.

In a July 2012 letter to the director of the program, Peter Rosenfeld, a board member of Coalition for Medical Marijuana—New Jersey (CMMNJ) stated that “Extremely strong scientific evidence has developed that shows that marijuana is one of the few efficacious treatments for neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain is pain that arises from damage to the brain, spinal cord or peripher- al nerves. A well-known type of neuropathic pain is “phantom limb” pain, but it also arises from autoimmune disorders as well as physical injury and irritation to the nerves. It is extremely resistant to most medical treat- ments. Even narcotics are relatively ineffective for this type of pain.”

ments for neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain is pain that arises from damage to the brain, spinal cord or peripher- al nerves. A well-known type of neuropathic pain is “phantom limb” pain, but it also arises from autoimmune disorders as well as physical injury and irritation to the nerves. It is extremely resistant to most medical treat- ments. Even narcotics are relatively ineffective for this type of pain.”

In New Jersey, conditions approved for a cannabis recommendation are: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; multiple sclerosis; terminal cancer; muscular dys- trophy; inflammatory bowel disease, including Crohn’s disease; and terminal ill- ness, if a physician determines a progno- sis of less than 12 months of life. If resist- ant to, or if the patient is intolerant to, conventional therapy, seizure disorder, including epilepsy; intractable skeletal muscular spasticity; and glaucoma are also approved. In addition, HIV, AIDS and cancer apply if accompanied by severe or chronic pain, severe nausea or vomiting.

For many with neuropathic pain, conventional treatment consists of heavy doses of narcotics, which make it tough to get through the day, let alone to work.

“This is a shame because I can go out and get any power- ful and potent pill there is whenever I get my prescriptions refilled, but I chose not to do that because of the effects and damage of those pills,” O’Brien said. “I prefer the safe and natural way. Everything else just clouds my mind and the pain is still there. Cannabis takes the pain away, and allows me to function in a normal and productive way.”

Because the science supporting cannabis as an analgesic for neuropathic pain is considerable, many state medical cannabis programs include it as a condition qualifying for

a recommendation. At about the same time that New Jersey’s program was signed into law, a study published in the Journal of the Canadian Medical Association reported clinical trial data for the efficacy of inhaled cannabis on pain intensity of 23 subjects with chronic post-traumatic or postsurgical neuropathic pain. All participants in the ran- domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial suffered from refractory pain for which conventional ther- apies had failed. In that study, researchers at McGill University in Montreal found that cannabis is effective as an analgesic. At the same time, investigators from the California Center for Medicinal Cannabis Research sum- marized results of four separate Food and Drug Administration ‘gold standard’- designed clinical trials demonstrating that inhaled marijuana is safe and effective for the treatment of neuropathic pain, which often goes untreated with conventional analgesics.

When hearings for the law were held, O’Brien went to Trenton six times — 85 miles each way — to testify, and he did testify four times. He spoke to doctors and legisla- tors. He spoke to the Senate Assembly and to Congress. When testifying, he made a strong impression by taking his shoes off to show the source of his suffering. “It amazes me that when they were making up the list of approved condi- tions, they did not hear me or see the tear in my eye when I was talking about the pain that I go through,” he said. “My voice was unheard. They passed a law that didn’t have me in it.”

While the law’s first draft included provisions to grow mar- ijuana, to make it more palatable to legislators, the ability for patients to grow their own medicine was also taken out.

“Had they left the law as it was originally intended, I would have had medicine for almost the past three years,” he said. “Had I been allowed to grow, I would not have been in chronic, debilitating pain that makes me throw up, that cripples me up and curls me into a fetal position on the floor crying. I cannot get legal access to the only thing that helps me. I’ve tried everything else. I tried oxycodone; I got addicted to them. I’ve tried all kinds of pills from doctors.”

O’Brien is not giving up. He has an appointment with a pain management specialist who treated him before and is now listed with the program as an approved physician. He will spend another few hundred dollars to see if this doctor will give him a recommendation to be in the state’s pro- gram.

“My main condition is neuropathy, which causes muscle spasticity, which is on the list of approved conditions,” he said. “This doctor has treated me before, knows my issues, and will be able to understand that neuropathy can cause the spasms because I’ve already been to him with that.”

After he receives a recommendation, he will pay for the

annual pension, according to the state’s Treasury website, is

$83,880. As director of the state’s medical cannabis pro- gram, his annual salary is $84,000. The state program is operating on a budget of less than $200,000.

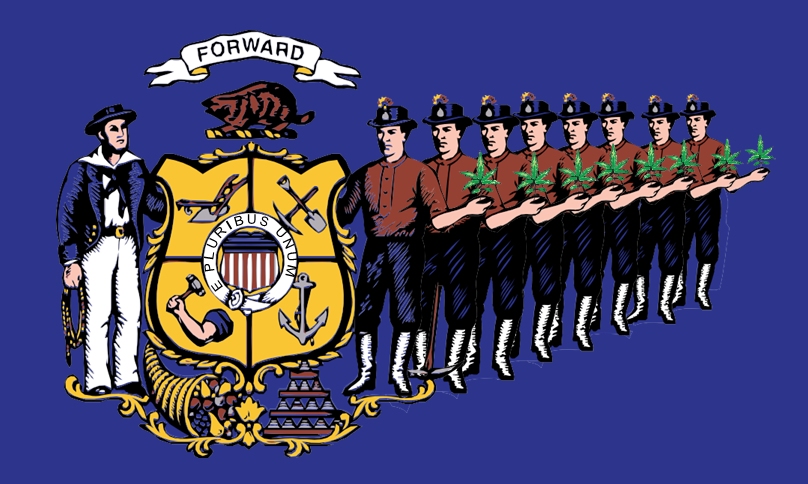

O’Brien, known for his experience in creating and manag- ing FBI and state criminal record systems, set up rigorous background check procedures for anyone involved with the ATCs. The move tightened regulation, but the vetting creat- ed more delays. In addition to background checks, dispen- saries will be subject to random monitoring, and State Police will be disposing of waste products from the grow operations.

U.S. Attorney for the district of New Jersey from 2002 to 2008, Gov. Christie maintains that the law is flawed and that the program should have been hospital-based. As the chief federal law officer for seven years, he understands the nature of the Schedule I status of marijuana in the Controlled Substances Act, and knows full well that a hos- pital-based program will never happen as long as a federal Prohibition is in place.

Gov. Christie blames the delays in implementation of the program on municipalities that do not want a plant consid- ered illegal by the federal government sold on their turf. With much rhetoric about the need to put safeguards in place to prevent any chance of the demon weed getting out to drug dealers in the black market, he has fanned the flames of fear in towns across the state. In interviews, he refers to recommending doctors in other states as quacks, and says that he’s worried about ending up with unscrupu- lous dispensary owners.

Local zoning boards did reject four of six proposed ATC grow sites and dispensary locations, citing weak oversight, among other things. Prior to voting on the ATC sites, resi- dents revealed an astounding lack of understanding of the value of medical cannabis. In a Camden County Courier Post letter to the editor prior to Maple Shade rejecting an ATC site, writer Diane Ludwig advised against an ATC in her community, stating, “A registered pharmacist told me that marijuana has only one medical quality, and that is the ability to ease nausea. For that purpose, pharmaceutical companies have extracted that one quality and put it into a capsule form called Marinol.”

By November, only one ATC, in Montclair was close to being open, and the owner of that business, Greenleaf Compassion Center, complained that state officials are pur- posefully stalling the program. Another, Compassionate Care Foundation, was given approval by town officials to open an ATC in Egg Harbor Township, but an extensive background check and zoning delays stalled that business. Another ATC found a location, but three more were having trouble finding homes for their operations.

A recent poll of New Jersey’s registered voters showed

medical marijuana identification card, which can run any- where from $20 to $200 and must be renewed every two years. The sliding fee scale recognizes a discount for enrollment in government assistance programs. Fully dis- abled, he should be able to get a break on that one expense.

Governor Christie Plays the Blame Game

Created to be opposite of California and Colorado programs that are often held up as patchworks of slapped-together regula- tion catering to small busi- ness “potrepreneurs,” New Jersey’s big business model features only six licenses granted to non- profit Alternative Treatment Centers (ATCs), each handling sales, testing and grow operations in-house. ATCs will be able to supply

patients with up to two ounces a month. They can grow

only three strains at a time, and all product must have less than 10 percent THC. Product is limited to raw plant material, lozenges and a topical cream.

In New Jersey, Gov. Christie, known as a law-and-order Republican, first used every trick in the book to stall the New Jersey Compassionate Use Medical Marijuana Act, which was signed into law on former Gov. Jon Corzine’s last day in office. After throwing up roadblocks for a year and a half, Christie surprised many in July 2011 when he announced the need to “begin work immediately.” Referring to the threats by U.S. Attorneys on the issue and a June 29 memo from Deputy Attorney General James Cole to prosecutors mentioning “an increase in the scope of commercial cultivation, sale, distribution and use of marijuana for purported medical purposes,” he said that he felt comfortable that the state’s heavily-regulated pro- gram would limit the risk of federal intervention. He said that “the need to provide compassionate pain relief to these citizens of our state outweighs the risks that we are taking in moving forward with the program.”

Publically, Christie states that he supports the law, but actions by state employees doing everything possible to delay the program speak louder than his words. A telling sign of his opinion of compassionate care was in his appointment of a former State Trooper to head the med- ical cannabis program. John O’Brien, no relation to patient Jack O’Brien, is a State Police veteran. O’Brien, 51, retired in June after 26 years with the State Police. His

that 86 percent support medical marijuana. While towns are not embracing the program, yet, advocates, patients, dispensary owners, and members of the medical commu- nity are laying the most blame for the dysfunctional roll- out on the state.

A suit filed on behalf of a patient in Superior Court in Trenton in April stated that those in charge of implemen- tation of the law — the DHSS commissioner and the director of the medical marijuana program were named as defendants — had been unable or unwilling to put the law into place. The suit maintained that the regulations writ- ten to govern the program are inconsistent with the law’s intent, and “intentionally designed with the intent to inter- fere with the medical marijuana program.”

In a September interview, Gov. Christie blamed the outgo- ing governor as well. He frequently states that the pro- gram was dumped in his lap.

“This bill was passed in a rush in January of 2010 because they wanted to get it in under the wire while Governor Corzine was still here,” he said. “The bill was without much thought – they didn’t know how they were going to enforce standards or anything else. We essentially had to remake the bill by regulation because it was so poorly written…It was signed at 3 o’clock in the morning by my predecessor on the morning I was being sworn in as Governor.”

Others take a different view.

“Christie has come out and said that they did rewrite the regulations,” said Stephen Cuspilich, a patient. “In my opinion, the law is the law; you cannot supersede it. He cannot go above and beyond the law. Christie is a cop. His job before he became governor was prosecutor, and so everyone knew that he was going to do everything in his power to not implement this law. His whole life has been putting people in jail for this, and now all of a sudden he’s going to sit back and say, “Here you go sick people?””

Cuspilich has severe Crohn’s disease that has been unre- sponsive to medication over the past 18 months. He can get a recommendation for legal cannabis with his condi- tion, but has not asked his doctor yet. He takes five pre- scriptions for pain medications and antibiotics to treat stomach ulcerations, and he is wary of asking his doctor to get involved. Physicians making recommendations are put on an online registry where they are swamped with cannabis inquiries. In addition, the state is also requiring physicians making recommendations to receive certifica- tion in pain management and addiction counseling.

New Jersey is the

only medical marijuana program in

the country that requires physicians to

join a special registry to recommend

marijuana, a requirement that seems

to be scaring many of the

state’s 30,000 physicians from becom-

ing involved. In September, CMMNJ issued a report about problems with the physician registration process. Vanessa Waltz, CMMNJ board member, called all 148 physicians listed on DHSS’s website for the program. According to the report, of the 99 doctor’s offices she was able to reach only 46 reported that they were actively accepting new patients; 30 offices were not accepting new patients but might in the future; and 23 offices reported that they were registered but not participating. In conversations with doctors and office personnel while calling around, Waltz found that the physicians had not been told that the physician registry would be published online.

“A good deal of the doctors on that registry are trying to get off,” Cuspilich said. “They only signed up for one or two of their own patients. My doctor is a well-regarded gastroenterologist, and he can see that the cannabis enables me to take less pain medication. He might want to help me, but that does not necessarily mean he wants to be a cannabis doctor.”

Cuspilich finds that cannabis helps his appetite and controls the pain in a way that pain pills cannot. With the help of the herbal remedy, he was able to cut his daily dose of mor- phine by two-thirds.

“I am a firm believer that if you can get a Percocet or a Xanex or a Valium, you should also be able to use cannabis because it is better for you,” he said. “This is the pharma- ceutical companies. They don’t want it. With cannabis, I was able to get rid of four prescriptions, and cut back on another two.”

He also testified in favor of the program several years back, and has nothing positive to say about obvious political maneuvers that shortchange the sick.

“I am a firm believer that if you can get a Percocet or a Xanex or a Valium, you should also be able to use cannabis because it is better for you,” he said. “This is the pharmaceutical companies. They don’t want it. With cannabis, I was able to get rid of four prescriptions, and cut back on another two.”

“That was a smart law with all of the regulations built into it,” he said. “There was no reason for the two years they waited to rewrite the regulations. Those regulations were already there.”

With a qualifying condition, Cuspilich knows that he will eventually get his card.

“I didn’t go through all of that time yelling and screaming up in Trenton for me not to take advantage of the pro- gram,” he said.

And if Jack O’Brien is granted a recommendation, it will probably be because a doctor recognizes that his neuro- pathic pain leads to spasms, which are approved. With Gov. Christie and the former police officer at the helm of New Jersey’s medical marijuana program, getting a new condition added to the list of qualifying conditions is a remote possibility.

Until he pays lots more money to secure the protection of legal access to a natural remedy, O’Brien will probably get by as he has for years.

“When I wake up in the

morning, there are

two things that I

do,” he said. “One of them

is to pray to my Father in

Heaven to give

me strength to get through

another day. The other

is to find access to pain relief without using FDA- approved medication that has

screwed up my intestines,

my liver, my kidneys,

my body. When I testified in

Trenton, I told them that if they didn’t put

pain on as an approved issue, I would

have to break the

law. I said, “I

am not a criminal for

goodness sake, but

you are making me one!”