Ryan’s War on Drugs

Photographer, Roger Leisner, The Maine Paparazzi

By Mary Lou Smart

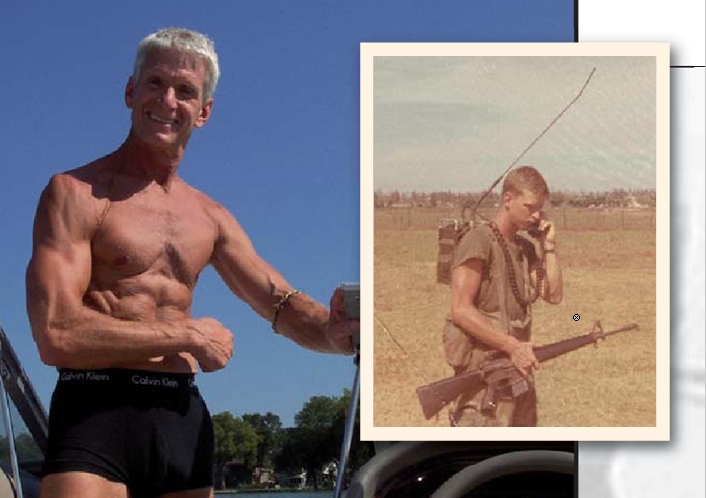

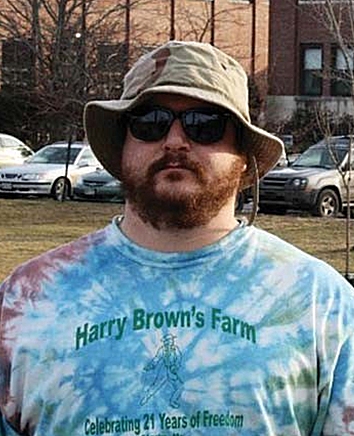

In his second deployment to Iraq in 2004, United States Marine Corp. Sgt. Ryan Begin lost his elbow to a roadside bomb.

The lower and upper sections of his arm were fused together. His arm is six inches shorter and no longer bends. Thirty-five surgeries, many at Maryland’s Bethesda Naval Hospital, left him addicted to prescription medication. His life was in a downward spiral marked by treatment at a Veteran’s Affairs (VA) facility, arrests and stays in mental institutions.

Begin’s pill load included Valium, OxyContin, morphine and Dextroamphetamine, a psychostimulant. By 2007, a time he refers to as his morphine phase, he was taking 100 pills a day.

“That didn’t even touch the pain,” he said. “That was just me trying to maintain, you know? I never did prescription pills before the military started shoving them down my throat. Of course you’re not going to get well when you’re being given Valium and speed. That’s not treatment. That’s “Here, eat these and shut up, and we’ll see you in a month.”

A Maine resident, Ryan was being treated at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Togus. About

a year ago, the

center refused to treat him when he reported that he’d begun using marijuana as medicine.

“I’ve been dealing with the VA since 2004, and they’ve known that I use marijuana the whole time,” he said. “They always listed it under recreational drug use. When I ran into a problem was when I told them that I’d gotten a referral and a medical marijuana card. At that point, my psychiatrist at the VA told me that I’d need to take a urine test or I would not be getting any more pills.”

Two other veterans treated by the Togus facility, also taken off of medication following their admission of mar- ijuana use, were subsequently shot and killed in alterca- tions with law enforcement officers.

The Fuzzy World of Pain Contracts

About 15 years ago, the federal government began requir- ing that physicians prescribing pain medications mandate that patients sign standard pain contracts stating that if it is found during a random drug test that they are taking certain illegal drugs, they will be denied treatment. While doctors withholding treatment for anything other than medical reasons is a topic that receives attention in the courts, actually denying treatment to a veteran in a VA hospital is seen as particularly cruel. In the civilian world, a person tossed out of a pain clinic can visit another pain clinic. After returning from service, many veterans rely on the VA as their sole venue for care.

In July 2010, the Department of Veterans Affairs, through the Veterans Health

Administration (VHA) issued Directive 2010-035. The directive acknowledged that laws in states authorizing the use of medical marijuana are contrary to federal law, that VA physicians recommending marijuana can lose the ability to prescribe controlled substances and be subject to criminal charges, and that marijuana can- not be used on VA property even in states that allow medical marijuana.

The VA, obligated by law to provide pain treatment to sol- diers injured in the line of duty, has issued directives out- lining guidance on access to and use of medical marijuana by veteran patients. One reason for the directives is that for decades a growing number of veterans have been med- icating with marijuana, lumped alongside dangerous nar- cotics in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act. While more and more states recognize the medicinal value of cannabis, the federal government does not.

In July 2010, the Department of Veterans Affairs, through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) issued Directive 2010-035. The directive acknowledged that laws in states authorizing the use of medical marijuana are contrary to federal law, that VA physicians recommending marijuana can lose the ability to prescribe controlled sub- stances and be subject to criminal charges, and that mari- juana cannot be used on VA property even in states that allow medical marijuana. The directive stated that VHA policy does not prohibit veterans participating in pro- grams of states that authorize medical marijuana from participating in VHA substance abuse programs, pain control programs or other clinical programs.

Lucky for Ryan, he had begun weaning himself off of the prescription medications when his VA physicians went against this directive and took him off of medication. The way it has been explained to him is that, despite the direc- tive, the VA can administratively allow patients to stay in pain management programs while taking them off of the opiates if they find out that they’re medicating with mari- juana, which is listed under federal law as a Schedule I drug with no medical benefit.

That is not how the directive was explained to Michael Krawitz, founding director of Veterans for Medical Cannabis Access. In 2010, after asking for clarification on the same subject, he received a letter from Department of Veteran Affairs Under Secretary for Health Dr. Robert Petzel, “Standard pain management agreements should draw a clear distinction between the use of illegal drugs and legal medical marijuana.”

Krawitz

maintains that

the VA is obligated

by law to pro- vide

pain treatment to soldiers injured in the line of duty. He

is not alone in believing that the pain contracts and

associated drug-testing provisions violate veterans Fourth Amendment right to be secure from unreasonable search; violate the Fifth Amendment by forcing veterans to testify against themselves when submitting to drug tests; and vio- late the Fourteenth Amendment provision for equal pro- tection under the law by targeting only pain patients.

While Krawitz has no problem signing a treatment attes- tation for pain management acknowledging he is who is says he is and agreeing to not misrepresent his history, he does not agree with the standard pain contract. Part of his problem with the contract is that the federal government’s stance in placing marijuana in Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act is particularly cruel in light of seriously ill patients that depend on the therapeutic benefit of cannabis. He maintains that marijuana’s classification is quite bizarre in light of Schedule I’s requirement that a drug have no currently accepted medical use in the United States. The inappropriate placement has been noted time and again, most notably in landmark rulings by two of the Drug Enforcement Administration’s (DEA) own Administrative Law Judges, Mary Ellen Bittner, in 2007, and Francis L. Young, in 1988, both of whom strongly favored more access for research and rescheduling in rul- ings that that were ignored by the DEA.

“It’s an interesting problem,” said Krawitz. “You’ve got these doctors that are not providing medical care. They’re acting as agents of the DEA, not as physicians. They’ve given up their Hippocratic Oath, and are not respecting these patients’ rights to medical care.”

Compassionate Care

Begin smoked marijuana in high school. He stopped when he joined the military, and started again following his injury. After years of VA drug use, arrests and stays at mental institutes, he decided to take matters into his own hands.

“The only thing that helped me was when I said, “Okay, I’ve given you guys seven years to try and treat me. Now I’m going to do my own research and figure this out on my own.””

Begin visited Dr. Dustin Sulak, an osteopathic physician who advises patients on healthier lifestyle choices. Well- documented chronic pain permitted Begin to receive a rec- ommendation to join Maine’s medical marijuana program. Prior to studying about cannabis, Begin understood that marijuana could help with anger and anxiety and stimulate appetite, but he didn’t understand its full potential. Gradually, he realized that cannabis eased the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). His life began to improve dramatically when issues such as recurrent night- mares tapered off.

“I was so out of balance from being on so many pills, that the marijuana was only helping with a portion of it,” he said. “It wasn’t until the spring, when the VA fully kicked me off my pills, that I found the true benefit of medical marijuana. Since then, every minute of my life’s been real- ly, really on the uphill. I can be medicated, but I’m still myself. I can still be who I am.”

One of many who have spent considerable time working to improve Maine’s program, Dr. Sulak sees many veter- ans that suffer with post-traumatic stress, and others expe- riencing anxiety and depression. He wants the rules and regulations that are being added to the law to include a reasonable process for adding qualifying medical condi- tions. As it stands, Maine’s law does not include PTSD as a qualifying condition.

“On a case by case basis, I’ve seen conditions that have proven to respond better to cannabis than to other treat- ments,” he said. “One of the exciting things that I’ve been finding in my practice, which hopefully we are going to be able to do scientific research on, is the use of cannabis instead of more dangerous pharmaceuticals.”

An integrative physician, Sulak sees

the potential of cannabis and other

alternative medicines and treatments as being capable of benefiting

society in many ways, including less reliance on pharmaceuticals, less visits to emergency

rooms, specialists, surgeons and doctors, and in more rewarding employment opportunities.

“I have seen a handful of patients that have left their depressing, soulless jobs in cubicles somewhere to become caregivers,” he said. “They have new lives dedicated to the service of others, steady incomes, and they find what they’re doing to be rewarding. When people find mean- ingful work, their lives get better, and that helps the heal- ing process.”

Begin, 32, medicates with cannabis, and looks forward to each day without pharmaceuticals. His mother, at first dis- couraged when she saw what he was doing, was amazed when she realized that her son had finally pulled away from drugs. She is now an advocate for medical cannabis.

He has helped two fellow veterans wean themselves off of pills, and works with advocates to try to help others. “We’re helping individuals get off of their medications so that they’re able to enjoy life again,” he said.

He did start a petition on www.change.org, to ask the DEA and the National Institute on Drug Abuse to stop blocking medical marijuana research for treating veterans with PTSD. The petition quickly gathered more than 16,000 signatures. His hope with this petition and other advocacy efforts is that people become empowered to share their experiences.

As he shares his positive experience with cannabis in help- ing to alleviate the overwhelming symptoms of PTSD, Begin urges others to do the same.

“It takes people to come forward and state that they use medical marijuana,” he said. “What we are doing is difficult, but that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. We are making waves.”